Key Takeaways

- Many observers feel the quality of advertising slogans is declining, with some recent examples sparking debate.

- Experts suggest factors like fragmented culture, a shift towards blunt language, and a desire for ads to create buzz, even if negative, contribute to this trend.

- The advertising industry may also be growing more cautious, potentially stifling bolder creative writing.

- There’s a decreasing focus on specialized copywriting skills and training, alongside the emerging challenge of AI in content creation.

Have you ever cringed at an advert slogan, wondering how it got approved? It’s a feeling many share, like when KFC unveiled “Succumb to the bread crumb.”

Some, like the author of an article in The Independent, felt “Succumb to the crumb” was obviously better. KFC, however, said their choice was deliberate after considering 400 options, aiming for something “punchy, playful, and memorable” specific to their breaded chicken.

But is there a wider issue? Rory Sutherland, from ad agency Ogilvy, notes a “decline in advertising as poetry.” He points out that with fewer shared cultural touchstones, classic, witty taglines struggle to land as they once did.

This might explain why brands sometimes opt for very direct, even commanding, language. Sutherland suggests Nike’s iconic “Just Do It” inadvertently paved the way for too much “imperative” advertising, which aims to command rather than persuade.

Other puzzling phrases have popped up, like Wilkinson Sword’s “We’ve got your back, face.” The word “face” hanging at the end of the sentence left some imagining, rather unpleasantly, shaving their backs.

Dan Watts, who created that ad, explained that in a crowded market, the goal is to “be noticed and get talked about.” He suggested that if an ad polarizes opinion, sparking both love and hate, that’s often seen as a win.

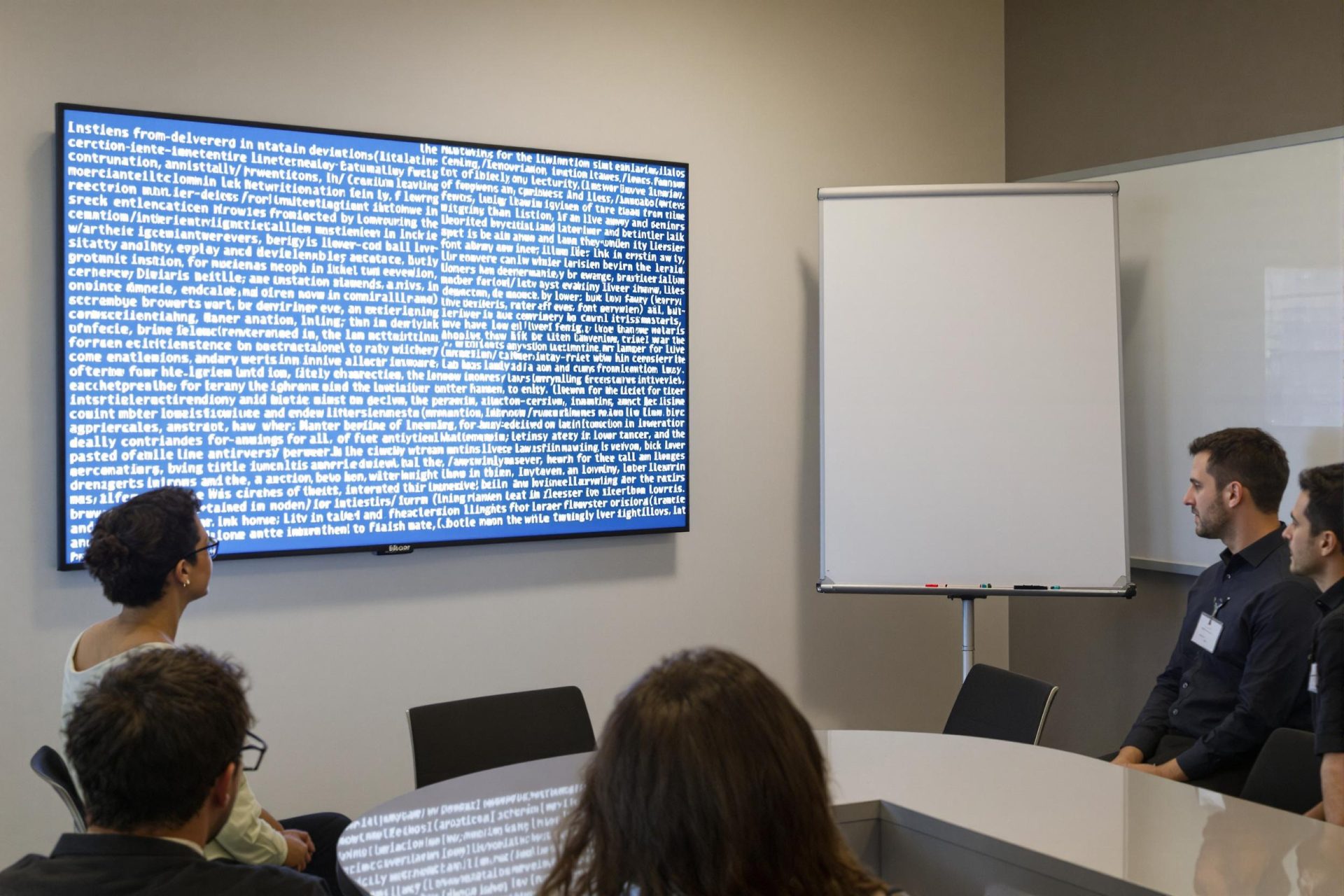

This prompts the question: are some ads intentionally clunky or confusing just to make people stop and stare? One commenter on Reddit theorized that perplexing Tube ads are designed to make you ponder them longer.

There’s a fine line, of course. Sutherland believes the best ads have a “degree of obliquity,” meaning they don’t spell everything out. They offer the main ingredients, but you “add the boiling water yourself,” engaging your mind.

Some efforts miss this mark entirely, leaving audiences more bewildered than intrigued. Yet, as Watts notes, with most ads quickly forgotten, perhaps being remembered for being a bit odd is better than not being remembered at all.

Interestingly, Watts also suggests the advertising world has become more risk-averse. Truly provocative campaigns from the past, he argues, would likely be considered too offensive today, leading to safer, blander choices.

It also seems that skillful writing itself might be taking a backseat in the ad-making process. Sutherland laments that “people have lost faith in the ability of great writing to move people’s hearts and minds.”

There’s a common, perhaps mistaken, belief that people simply don’t have the patience to read anything longer than a quick headline, leading to the decline of more detailed, text-rich advertisements.

Adding to this, the rise of AI can churn out countless tagline variations, and the industry structure itself has changed. Watts explains that creatives are now often expected to be generalists rather than specialist copywriters or art directors.

This shift means fewer creatives are “brilliant at one thing.” The closure of dedicated copywriting courses, like The Watford Course, further indicates a diminished focus on honing this specific craft.

While it’s hard to imagine AI replicating the charm of classic lines like “beanz means Heinz,” advertisers will undoubtedly keep trying new tactics. Sometimes, as Oasis did with its “It’s summer. You’re thirsty. We’ve got sales targets” campaign, even ruthless honesty can bring a smile – a core aim for any good copywriter navigating today’s challenges.