Key Takeaways

- Global data center energy use is rapidly increasing, driven by AI and digital services.

- The International Energy Agency projects this energy consumption could double by 2030.

- This surge challenges climate goals, potentially leading to more fossil fuel reliance.

- Some regions are implementing regulations to manage data center growth and energy use.

- Climate tech startups see opportunities but face reduced funding as investment shifts towards AI.

- Despite funding shifts, AI and climate tech can work together, with AI potentially speeding up climate solutions.

- Experts suggest policies like improved chip efficiency, on-device AI, and energy/carbon credit trading systems can help.

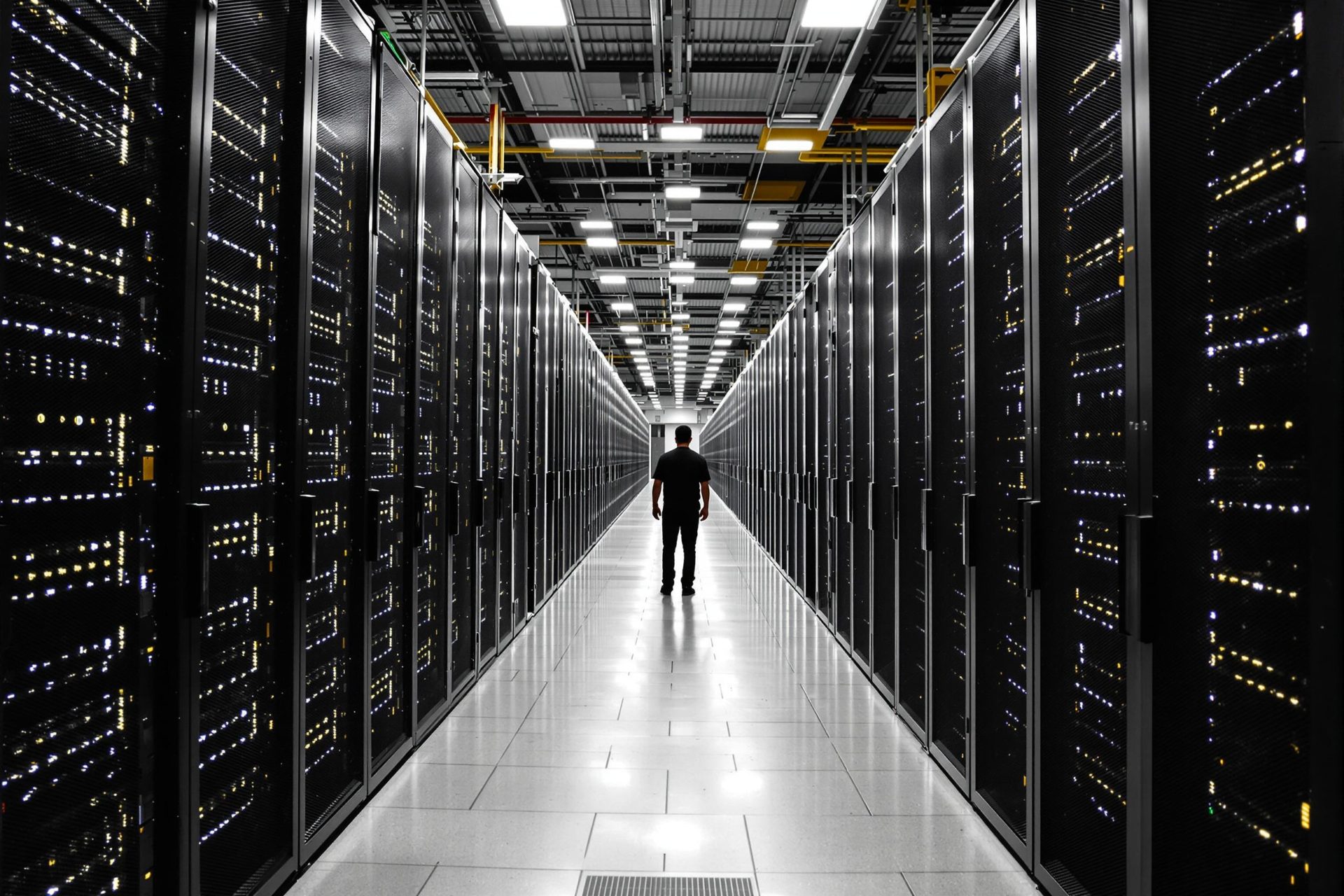

The global appetite for data centers is surging, fueled largely by the expansion of artificial intelligence and digital services. This boom comes with a significant energy cost.

Energy consumption by data centers worldwide is climbing fast. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), these facilities used about 1.5% of global electricity in 2024, and demand has grown 12% annually over the past five years.

Hyperscale data centers, the massive facilities run by major tech companies, have doubled their energy use recently. The IEA forecasts global data center electricity needs will more than double again by 2030.

To put it in perspective, a single large data center can use as much power as 100,000 North American homes. New AI-focused centers might need 20 times that amount. Tech giants like Microsoft, Meta, Google, and Amazon committed around $125 billion to AI data centers in just eight months of 2024, as noted by JPMorgan.

This escalating energy demand creates both problems and possibilities. Some U.S. utilities are planning new fossil fuel power plants or extending the life of coal plants to meet the need, according to Canary Media. This could seriously hinder efforts to reduce carbon emissions.

Globally, some areas are responding with stricter rules. Amsterdam paused new data center construction to focus on sustainability, while Singapore introduced rules for higher server room temperatures to cut cooling energy, though this might affect equipment lifespan.

Climate tech startups see a chance to help decarbonize this digital infrastructure. For instance, 280 Earth, emerging from Google’s innovation lab, secured funding to capture carbon emissions for major companies. Other new ventures are working on more efficient power systems for data centers.

However, these climate tech innovators face hurdles. BloombergNEF data shows global climate tech funding dropped significantly in 2024 for the third year running, even as overall venture capital investment grew. A massive influx of cash into AI companies, nearly $100 billion in 2024, seems to have diverted funds from decarbonization efforts.

But this doesn’t mean AI and climate solutions are entirely at odds. Many believe AI can actually accelerate climate technology development. Investment sectors linked to AI infrastructure, like energy and buildings, saw funding increases despite the general climate tech downturn.

Indeed, a Sightline Climate report highlighted that several of the largest climate tech deals in 2024 involved businesses focused on sustainable data centers.

While top climate tech deals focused on batteries in 2023, the average deal size decreased in 2024. To boost the sector, governments could support R&D and offer tax incentives for more energy-efficient AI chips.

Innovations at the chip level can drastically cut power use. Companies in China, the U.S., and South Korea are developing chips with novel designs to slash energy needs. Moving AI processing from large data centers to individual devices (“on-device AI”) could also cut energy use dramatically.

Experts suggest implementing energy credit trading systems could also help. Such systems would reward companies for using efficient hardware or running tasks when renewable energy is plentiful.

Currently, carbon credit trading systems are inconsistent. While the EU has a system, comprehensive nationwide frameworks are lacking in most major economies, including the U.S., where only a few states have compliance markets.

Expanding both energy and carbon credit markets could incentivize investment in low-carbon computing, ensuring that the infrastructure powering future AI also supports climate goals instead of relying on fossil fuels.